In our earlier submit, we recognized the diploma to which flood maps within the Federal Reserve’s Second District are inaccurate. On this submit, we use our knowledge on the accuracy of flood maps to look at how banks lend in “inaccurately mapped” areas, once more specializing in the Second District particularly. We discover that banks are seemingly conscious of poor-quality flood maps and are usually much less prone to lend in such areas, thereby demonstrating a level of flood danger administration or danger aversion. This propensity to keep away from lending in inaccurately mapped areas might be seen in jumbo in addition to non-jumbo loans, as soon as we account for a sequence of confounding results. The outcomes for the Second District largely mirror these for the remainder of the nation, with inaccuracies resulting in comparable reductions in lending, particularly amongst non-jumbo loans.

Inaccurate Flood Maps

As supervisor of the Nationwide Flood Insurance coverage Program (NFIP), the Federal Emergency Administration Company (FEMA) works with communities to attract maps that denote the danger of a catastrophic flood occurring a minimum of as soon as in 100 years. Areas which can be liable to such flooding are thought of to have a 1 p.c (or extra) annual flood danger. An essential implication of being in a flood zone is the insurance coverage requirement for mortgage debtors. Particularly, any mortgage applicant in a flood zone whose mortgage meets sure standards—comparable to being eligible for securitization or being made by a monetary establishment—should purchase flood insurance coverage. This system—in addition to the implications for the mortgage market—are mentioned in earlier Liberty Avenue Economics posts on this sequence (see right here or right here).

In our earlier submit, we mentioned the truth that sure flood maps could also be inaccurate. These inaccuracies come up partly as a result of it takes time to replace the maps within the face of local weather change, and partly due to enhancements and different modifications made to native infrastructure and constructing supplies that take time to be mirrored in official flood maps. We use property-level info on flood injury publicity from CoreLogic in addition to digitized flood maps for 2022 to outline inaccuracies (as described in our earlier submit).

Maps might be inaccurate in one in every of two methods: both they designate an excessive amount of of an space as being a “flood danger,” or they designate too little. For the needs of this submit, we focus solely on the latter situation and outline two classes of inaccuracy. If a property faces vital flooding injury (highest injury quartile) however isn’t “mapped” right into a flood zone, its map is “very inaccurate.” If a property faces average injury however isn’t lined by a flood zone, its map is solely “inaccurate.” All different properties are both precisely mapped or appropriately excluded from a flood map as a result of they face no flood danger. We collapse this knowledge on the census-tract degree after which calculate the share of every census tract that’s “very inaccurate” and “inaccurate” within the analyses under. This considerably coarse evaluation is important as we can not use address-specific mortgage knowledge. As earlier than, we concentrate on properties within the Second District in addition to the nation as a complete for mortgage functions in 2019 and 2020.

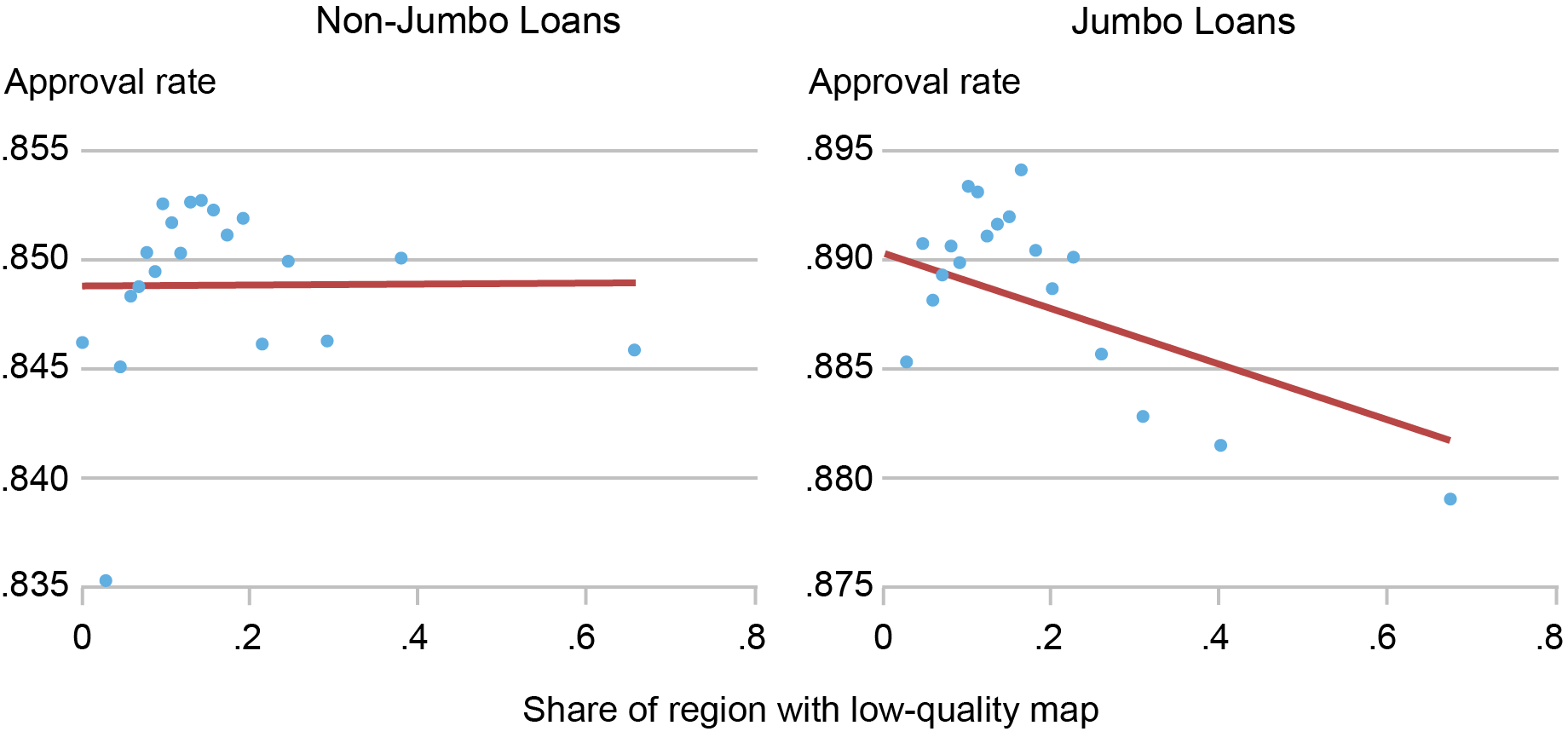

A key query is whether or not lenders are conscious of—and aware of—these inaccuracies. To this finish, we make use of House Mortgage Disclosure Act (HMDA) mortgage knowledge on the census tract degree. We first have a look at easy correlations between the share of a census tract that’s “very inaccurate” and the acceptance charge of mortgage functions. Within the left panel of the chart under, we see that for non-jumbo (“conforming”) loans, there may be little or no relationship between the 2 variables. That is presumably a consequence of many of those loans transferring off of a financial institution’s stability sheet within the close to time period. Nevertheless, jumbo loans, which usually tend to be retained by banks, present a way more unfavourable correlation, as proven in the correct panel. In different phrases, census tracts through which a larger proportion of properties are inaccurately mapped see a decrease acceptance charge for jumbo functions, on common.

Lending in Areas with Inaccurate Flood Maps

Sources: Authors’ calculations; Federal Emergency Administration Company (FEMA); House Mortgage Disclosure Act (HMDA) knowledge; CoreLogic.

Notes: This chart reveals binscatter plots that relate the share of a census tract that’s “very inaccurately” mapped to the mortgage acceptance charge. It consists of time controls however no different changes. Information cowl the Second District excluding Puerto Rico and the U.S. Virgin Islands and are break up into conforming (non-jumbo) and non-conforming (jumbo) loans.

This result’s presumably a mirrored image of financial institution danger administration. Retaining a mortgage that’s topic to flood danger however that won’t have flood insurance coverage (or might even be ineligible for insurance coverage from the NFIP if the neighborhood doesn’t take part) might symbolize too dangerous a proposition. Nevertheless, since a complete host of different elements go right into a mortgage utility determination, we use regression evaluation to manage for these different elements.

The Impact of Flood Map Accuracy on Lending

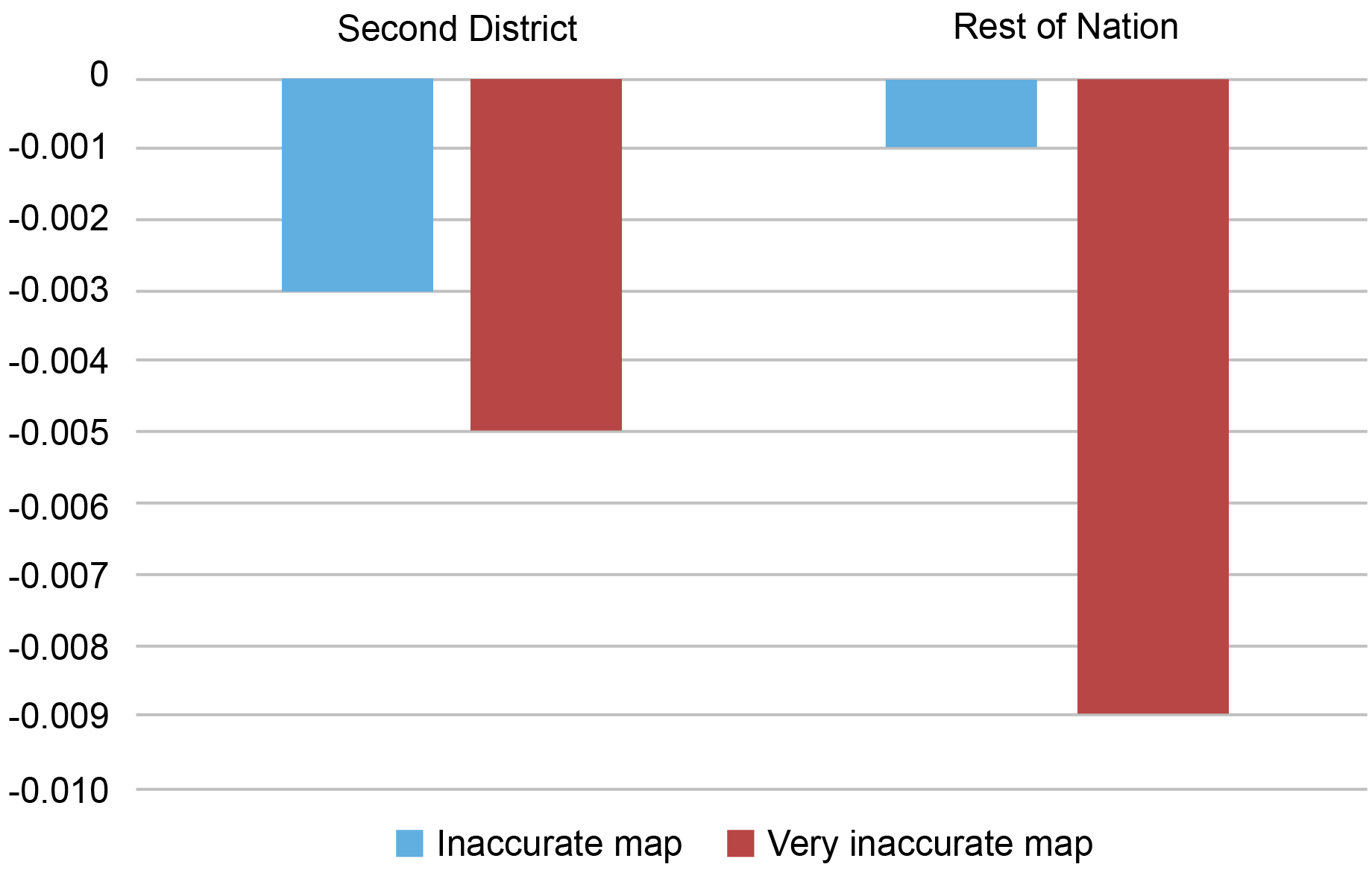

Our final result variable is the mortgage acceptance chance as measured by a variable that takes the worth of “1” if an utility is accepted. We regress the mortgage acceptance chance on utility quantities in {dollars}, borrower traits (revenue, gender, race, and loan-to-income ratio), the county the place the property is positioned interacted with time, the common census tract revenue, previous flood damages, and a number of different traits. We additionally embrace a variable that denotes the share of properties in a census tract which can be (1) “inaccurately mapped” or (2) “very inaccurately mapped.” Outcomes are proven within the chart under.

Impact of Inaccurate Maps, after Accounting for Borrower and Area Traits

Sources: Authors’ calculations; Federal Emergency Administration Company (FEMA); House Mortgage Disclosure Act (HMDA) knowledge; CoreLogic.

Notes: This chart reveals the important thing coefficients for a linear chance regression that relates mortgage acceptance charges (1= accepted by borrower and financial institution) to a number of mortgage, area, and borrower traits, in addition to key variables that denote the share of properties in a census tract which can be “inaccurately mapped” or “very inaccurately mapped.” It reveals the Second District (excluding Puerto Rico and the U.S. Virgin Islands) and the remainder of the nation individually and focuses solely on the coefficients of curiosity for non-jumbo loans.

We discover that financial institution loans in areas which have inaccurate maps have a considerably decrease acceptance charge, all else equal. Areas which have very inaccurate maps see a extra pronounced discount in acceptances. If we embrace borrower traits—particularly borrower revenue and loan-to-value ratios—the connection between the share of inaccurately mapped properties and mortgage acceptance charges turns into much less unfavourable amongst jumbo loans than within the uncooked correlation. This can be a mirrored image of the power of those debtors to make a bigger down cost to assist offset the financial institution’s perceived danger.

It’s price mentioning that whereas these reductions within the acceptance charges are statistically vital, they’re small relative to the consequences of applicant revenue or wealth. A Second District neighborhood through which 10 p.c of all properties are inaccurately mapped might even see a discount of three p.c in acceptance charges. A ten p.c drop in revenue would see a rejection response that’s fourfold bigger. Our outcomes doubtless mirror some residual financial institution danger aversion—not all conforming loans are securitized, in any case. Furthermore, banks which can be conscious of the incorrect mapping doubtless anticipate maps to alter following future updates. Since lenders/servicers have to make sure that pre-existing debtors who’re newly mapped into flood zones purchase insurance coverage after a grace interval expires, they might be ex ante unwilling to lend to those inaccurately mapped households. Alternatively, banks could also be anxious in regards to the capability of the marginal borrower to make the required insurance coverage funds.

The response of lenders to inaccurate maps within the Second District is akin to that within the nation as a complete, particularly amongst non-jumbo debtors. The response to very inaccurate maps is considerably stronger in southern states, which can mirror elevated danger of catastrophic flooding. Whereas we don’t totally account for a variety of region-specific elements that will differ between the Second District and the remainder of the nation, we nonetheless discover that financial institution responses to inaccuracies are broadly comparable—that’s to say, they scale back lending. This means that financial institution reactions to inaccurate maps should not state-specific however usually tend to be a mirrored image of basic danger aversion.

Concluding Remarks

We discover that banks are considerably aware of inaccurately mapped areas. They’re much less keen to lend in areas with poor flood maps, even when these loans might be securitized. On this regard, the Second District isn’t any totally different than the remainder of the nation. Whereas financial institution reactions to inaccurate maps are small, the presence of statistically significant lending variations implies that banks handle and are conscious of flood danger, a minimum of to some extent. The subsequent submit on this sequence exploits the newly up to date maps to look at whether or not corporations take flood danger under consideration when selecting their enterprise areas.

Kristian Blickle is a monetary analysis economist in Local weather Threat Research within the Federal Reserve Financial institution of New York’s Analysis and Statistics Group.

Katherine Engelman is a former knowledge scientist within the Information and Analytics Workplace within the Financial institution’s Expertise Group.

Theo Linnemann is a knowledge scientist within the Information and Analytics Workplace within the Financial institution’s Expertise Group.

João A.C. Santos is the director of Monetary Intermediation Coverage Analysis within the Federal Reserve Financial institution of New York’s Analysis and Statistics Group.

The best way to cite this submit:

Kristian S. Blickle, Katherine Engelman, Theo Linnemann, and João A. C. Santos, “How Do Banks Lend in Inaccurate Flood Zones within the Fed’s Second District?,” Federal Reserve Financial institution of New York Liberty Avenue Economics, November 13, 2023, https://libertystreeteconomics.newyorkfed.org/2023/11/how-do-banks-lend-in-inaccurate-flood-zones-in-the-feds-second-district/.

Disclaimer

The views expressed on this submit are these of the writer(s) and don’t essentially mirror the place of the Federal Reserve Financial institution of New York or the Federal Reserve System. Any errors or omissions are the duty of the writer(s).