This text is an on-site model of our Unhedged publication. Enroll right here to get the publication despatched straight to your inbox each weekday

Good morning. The retail value of beef within the US has hit a report, pushed by droughts throughout American cattle nation. We’ve tried to remain calm about inflation over the previous few years, but when steak turns into unaffordable, the Unhedged staff goes to succumb to financial panic (extra rational ideas on the hyperlink between inflation and sentiment could be discovered beneath). Electronic mail us: robert.armstrong@ft.com and ethan.wu@ft.com.

Dangerous client sentiment isn’t a surprise

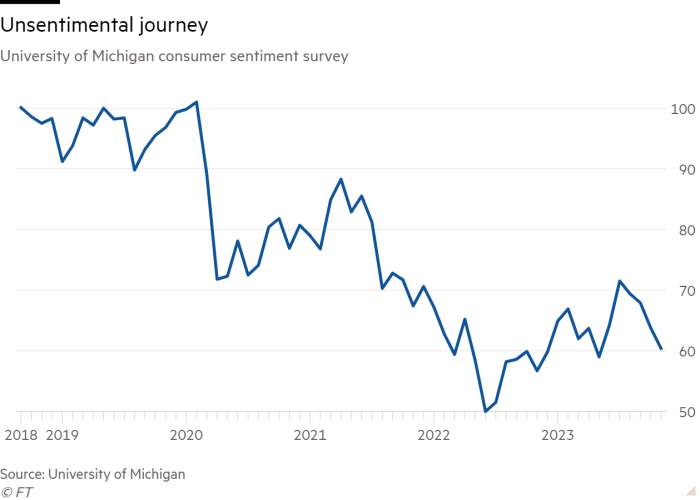

A standard grievance amongst Democratic partisans is that Joe Biden and his occasion don’t get credit score for a powerful financial system, which options employment and actual development ranges forward of these seen in the remainder of the developed world. And sentiment will not be getting any higher even because the inflation fee grinds down and markets stage a restoration. The preliminary November studying for the College of Michigan client sentiment survey was 60.4, the bottom since Could and in keeping with the depressing sideways development that extends again virtually two years:

At Unhedged, we don’t discover this shocking in any respect. Costs are up virtually 20 per cent for the reason that pandemic started; the value of meals is up 24 per cent, power 37 per cent. That this could make the world really feel malign and unpredictable is barely pure. It doesn’t matter that wages have, on common, saved tempo. If I get a increase, I earned it; it isn’t a mere symptom of a powerful nationwide output. If the value of meals is spiralling upwards, that’s a nasty financial system, or the federal government’s fault. Nor does it matter that the speed of inflation has fallen. Individuals don’t see the speed of change on the facet of a gallon of milk. They see a value that’s vastly completely different from what it as soon as was.

Even so, one may ask why sentiment has not improved whilst arguably an important value of all — petrol — has come down up to now six weeks. That may be defined by the truth that whereas client sentiment can fall shortly, it’s sluggish to recuperate. It is sort of a private popularity: constructed slowly, gone straight away. Discover how sentiment (the blue line within the chart beneath) fell in a short time within the recessions of 1991, 2001 and 2008, however then took its time coming again to a persistently excessive stage.

The present second can appear a bit odd inasmuch as client sentiment and modifications in actual spending (the pink line) appear to trace each other traditionally however at the moment are coming aside. How can individuals really feel that instances are dangerous, and but maintain spending merrily? Effectively, if you happen to settle for that folks imagine that modifications in nominal costs are one thing dangerous in and of themselves, no matter nominal incomes are doing, that thriller goes away. Sentiment and spending would not have to journey collectively.

Yield curve management: a lesson (or warning) from Japan

Final week in Unhedged, Jenn Hughes requested if yield curve management may attain the US. This could be an excessive consequence, however it takes solely a bit creativeness to see how we’d get there. A traditionally massive peacetime fiscal deficit is immediately paired with considerably constructive actual rates of interest; politicians stay hostile to tax will increase or spending cuts; bond buyers develop nervous, and an exterior shock sends yields hovering. The central financial institution concludes that monetising the debt is the least-worst possibility.

Does that make you’re feeling anxious? Fiscal doves have a chilled response: Japan. There, public-sector debt runs above thrice GDP, and the Financial institution of Japan has purchased a lot of the authorities bonds for a decade with out inflicting a catastrophe. And now Japan’s financial system is lastly experiencing inflation and nominal wage development, whereas companies are slowly reforming themselves. Actual GDP is on monitor for two per cent development this 12 months, tasks Marcel Thieliant of Capital Economics. Extraordinary fiscal and financial interventions seem to have purchased Japan the time it wanted.

However a new paper by YiLi Chien of the St Louis Fed, Harold Cole of the College of Pennsylvania and Hanno Lustig of Stanford, means that Japan’s instance will not be as encouraging because it seems. Chien, Cole and Lustig argue that Japan has staved off a fiscal disaster by, in impact, working a large carry commerce to finance itself over the previous three many years.

In a typical yen carry commerce, buyers benefit from low Japanese charges by borrowing yen, exchanging them for {dollars}, and investing the {dollars} at increased US charges. That is dangerous, as a result of both forex can transfer towards you. However it may be profitable.

The Japanese authorities have performed one thing related by financing dangerous investments with artificially low-cost financing offered by Japan’s households, utilizing the banking sector as a intermediary. The authors (hereafter abbreviated CCL) see two issues. Japan’s fiscal and financial set-up acts as an enormous switch from the younger, poor and financially unsophisticated to aged pensioners, the financially savvy and the state; and the commerce may finally fail.

CCL current a composite steadiness sheet for the Japanese public sector, together with the central authorities, the BoJ and the state pension fund. It has modified rather a lot for the reason that Nineteen Nineties (all figures are a share of GDP):

Observe, on the liabilities facet, the roughly 100 proportion level enhance in financial institution reserves and, on the belongings facet, the rise in equities and international securities.

CCL supply the next idea of the case:

-

The Japanese public sector borrows at shorter durations, through bonds and payments (common length of seven years). Most significantly, the central financial institution points financial institution reserves in return for bonds, preserving rates of interest low as a part of quantitative easing. That is debt monetisation.

-

Via the state pension fund, the general public sector invests in longer-duration dangerous belongings resembling equities and international securities (common length of 23 years). These positions should not hedged for rate of interest or FX danger, letting the state “harvest carry commerce danger premia”.

-

The BoJ’s QE pins authorities bond yields, preserving authorities borrowing prices low. This lets the federal government subject overpriced bonds to lift contemporary debt, as a result of non-public buyers know they will merely flip round and promote them to the BoJ.

-

The general public sector is levered lengthy length; it positive aspects when charges go down. This commerce pays rather a lot: as a lot as 3 per cent of GDP a 12 months. This roughly matches the hole between taxes and authorities spending guarantees (excluding curiosity funds), round 3.5 per cent of GDP.

It’s a carry commerce the place the investor units their very own funding prices. The extra fiscal capability created by low-cost funding — and the fiscal penalty if funding prices rise — provides the general public sector a powerful incentive to peg actual charges low.

However whereas the general public sector positive aspects, many Japanese lose. Most households, particularly youthful ones, barely personal monetary belongings. Wealth is disproportionately saved in financial institution deposits, to the tune of 200 per cent of GDP, which haven’t any length and pay basically nothing. Some Japanese do put money into shares (38 per cent of GDP) or have a personal pension or insurance coverage plan (98 per cent of GDP). However general, surpluses are being moved from deposit-holding Japanese to the state and pensioners.

Is that this set-up steady in the long term? We put that query to Stanford’s Lustig, who argues it isn’t. He attracts an analogy to underfunded US pension schemes which, to enhance funding ratios, take extra dangers on the asset facet of the steadiness sheet within the hope of higher returns. The hazard is that obligatory liabilities are being matched with belongings that may lose worth. “The Japanese authorities has made all these risk-free guarantees to pensioners and issued bonds which can be speculated to be risk-free. However on the asset facet they’re growing fairness publicity fairly dramatically,” he says. “This doesn’t finish nicely except you’re extraordinarily fortunate. You may get a nasty draw of fairness returns, and find yourself with a good larger shortfall.”

Requested what classes he attracts from Japan for a US context, Lustig added: “Central banks can flatter your estimates of fiscal capability fairly a bit. However after they step again, you realise it’s a lot smaller than you thought it was.” (Ethan Wu)

One good learn

“Removed from being an fairness recreation, non-public fairness is a debt recreation by which the economics are pushed by the price of cash.”

FT Unhedged podcast

Can’t get sufficient of Unhedged? Take heed to our new podcast, hosted by Ethan Wu and Katie Martin, for a 15-minute dive into the most recent markets information and monetary headlines, twice per week. Make amends for previous editions of the publication right here.

Beneficial newsletters for you

Swamp Notes — Knowledgeable perception on the intersection of cash and energy in US politics. Enroll right here

Chris Giles on Central Banks — Your important information to cash, rates of interest, inflation and what central banks are pondering. Enroll right here